|

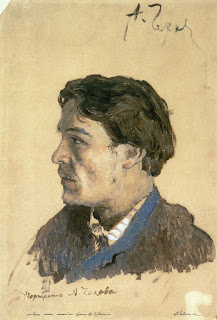

| Portrait of Chekhov by Isaak Levitan 1886 |

A PECULIAR MAN

Between twelve and one at night a tall gentleman, wearing a top-hat and a coat with a hood, stops before the door of Marya Petrovna Koshkin, a midwife and an old maid. Neither face nor hand can be distinguished in the autumn darkness, but in the very manner of his coughing and the ringing of the bell a certain solidity, positiveness, and even impressiveness can be discerned. After the third ring the door opens and Marya Petrovna herself appears. She has a man's overcoat flung on over her white petticoat. The little lamp with the green shade which she holds in her hand throws a greenish light over her sleepy, freckled face, her scraggy neck, and the lank, reddish hair that strays from under her cap. "Can I see the midwife?" asks the gentleman. "I am the midwife. What do you want?" The gentleman walks into the entry and Marya Petrovna sees facing her a tall, well-made man, no longer young, but with a handsome, severe face and bushy whiskers. "I am a collegiate assessor, my name is Kiryakov," he says. "I came to fetch you to my wife. Only please make haste." "Very good . . ." the midwife assents. "I'll dress at once, and I must trouble you to wait for me in the parlour." Kiryakov takes off his overcoat and goes into the parlour. The greenish light of the lamp lies sparsely on the cheap furniture in patched white covers, on the pitiful flowers and the posts on which ivy is trained. . . . There is a smell of geranium and carbolic. The little clock on the wall ticks timidly, as though abashed at the presence of a strange man. "I am ready," says Marya Petrovna, coming into the room five minutes later, dressed, washed, and ready for action. "Let us go." "Yes, you must make haste," says Kiryakov. "And, by the way, it is not out of place to enquire--what do you ask for your services?" "I really don't know . . ." says Marya Petrovna with an embarrassed smile. "As much as you will give." "No, I don't like that," says Kiryakov, looking coldly and steadily at the midwife. "An arrangement beforehand is best. I don't want to take advantage of you and you don't want to take advantage of me. To avoid misunderstandings it is more sensible for us to make an arrangement beforehand." "I really don't know--there is no fixed price." "I work myself and am accustomed to respect the work of others. I don't like injustice. It will be equally unpleasant to me if I pay you too little, or if you demand from me too much, and so I insist on your naming your charge." "Well, there are such different charges." "H'm. In view of your hesitation, which I fail to understand, I am constrained to fix the sum myself. I can give you two roubles." "Good gracious! . . . Upon my word! . . ." says Marya Petrovna, turning crimson and stepping back. "I am really ashamed. Rather than take two roubles I will come for nothing . . . . Five roubles, if you like." "Two roubles, not a kopeck more. I don't want to take advantage of you, but I do not intend to be overcharged." "As you please, but I am not coming for two roubles. . . ." "But by law you have not the right to refuse." "Very well, I will come for nothing." "I won't have you for nothing. All work ought to receive remuneration. I work myself and I understand that. . . ." "I won't come for two roubles," Marya Petrovna answers mildly. "I'll come for nothing if you like." "In that case I regret that I have troubled you for nothing. . . . I have the honour to wish you good-bye." "Well, you are a man!" says Marya Petrovna, seeing him into the entry. "I will come for three roubles if that will satisfy you." Kiryakov frowns and ponders for two full minutes, looking with concentration on the floor, then he says resolutely, "No," and goes out into the street. The astonished and disconcerted midwife fastens the door after him and goes back into her bedroom. "He's good-looking, respectable, but how queer, God bless the man! . . ." she thinks as she gets into bed. But in less than half an hour she hears another ring; she gets up and sees the same Kiryakov again. "Extraordinary the way things are mismanaged. Neither the chemist, nor the police, nor the house-porters can give me the address of a midwife, and so I am under the necessity of assenting to your terms. I will give you three roubles, but . . . I warn you beforehand that when I engage servants or receive any kind of services, I make an arrangement beforehand in order that when I pay there may be no talk of extras, tips, or anything of the sort. Everyone ought to receive what is his due." Marya Petrovna has not listened to Kiryakov for long, but already she feels that she is bored and repelled by him, that his even, measured speech lies like a weight on her soul. She dresses and goes out into the street with him. The air is still but cold, and the sky is so overcast that the light of the street lamps is hardly visible. The sloshy snow squelches under their feet. The midwife looks intently but does not see a cab. "I suppose it is not far?" she asks. "No, not far," Kiryakov answers grimly. They walk down one turning, a second, a third. . . . Kiryakov strides along, and even in his step his respectability and positiveness is apparent. "What awful weather!" the midwife observes to him. But he preserves a dignified silence, and it is noticeable that he tries to step on the smooth stones to avoid spoiling his goloshes. At last after a long walk the midwife steps into the entry; from which she can see a big decently furnished drawing-room. There is not a soul in the rooms, even in the bedroom where the woman is lying in labour. . . . The old women and relations who flock in crowds to every confinement are not to be seen. The cook rushes about alone, with a scared and vacant face. There is a sound of loud groans. Three hours pass. Marya Petrovna sits by the mother's bedside and whispers to her. The two women have already had time to make friends, they have got to know each other, they gossip, they sigh together. . . . "You mustn't talk," says the midwife anxiously, and at the same time she showers questions on her. Then the door opens and Kiryakov himself comes quietly and stolidly into the room. He sits down in the chair and strokes his whiskers. Silence reigns. Marya Petrovna looks timidly at his handsome, passionless, wooden face and waits for him to begin to talk, but he remains absolutely silent and absorbed in thought. After waiting in vain, the midwife makes up her mind to begin herself, and utters a phrase commonly used at confinements. "Well now, thank God, there is one human being more in the world!" "Yes, that's agreeable," said Kiryakov, preserving the wooden expression of his face, "though indeed, on the other hand, to have more children you must have more money. The baby is not born fed and clothed." A guilty expression comes into the mother's face, as though she had brought a creature into the world without permission or through idle caprice. Kiryakov gets up with a sigh and walks with solid dignity out of the room. "What a man, bless him!" says the midwife to the mother. "He's so stern and does not smile." The mother tells her that _he_ is always like that. . . . He is honest, fair, prudent, sensibly economical, but all that to such an exceptional degree that simple mortals feel suffocated by it. His relations have parted from him, the servants will not stay more than a month; they have no friends; his wife and children are always on tenterhooks from terror over every step they take. He does not shout at them nor beat them, his virtues are far more numerous than his defects, but when he goes out of the house they all feel better, and more at ease. Why it is so the woman herself cannot say. "The basins must be properly washed and put away in the store cupboard," says Kiryakov, coming into the bedroom. "These bottles must be put away too: they may come in handy." What he says is very simple and ordinary, but the midwife for some reason feels flustered. She begins to be afraid of the man and shudders every time she hears his footsteps. In the morning as she is preparing to depart she sees Kiryakov's little son, a pale, close-cropped schoolboy, in the dining-room drinking his tea. . . . Kiryakov is standing opposite him, saying in his flat, even voice: "You know how to eat, you must know how to work too. You have just swallowed a mouthful but have not probably reflected that that mouthful costs money and money is obtained by work. You must eat and reflect. . . ." The midwife looks at the boy's dull face, and it seems to her as though the very air is heavy, that a little more and the very walls will fall, unable to endure the crushing presence of the peculiar man. Beside herself with terror, and by now feeling a violent hatred for the man, Marya Petrovna gathers up her bundles and hurriedly departs. Half-way home she remembers that she has forgotten to ask for her three roubles, but after stopping and thinking for a minute, with a wave of her hand, she goes on. AT THE BARBER'S MORNING. It is not yet seven o'clock, but Makar Kuzmitch Blyostken's shop is already open. The barber himself, an unwashed, greasy, but foppishly dressed youth of three and twenty, is busy clearing up; there is really nothing to be cleared away, but he is perspiring with his exertions. In one place he polishes with a rag, in another he scrapes with his finger or catches a bug and brushes it off the wall. The barber's shop is small, narrow, and unclean. The log walls are hung with paper suggestive of a cabman's faded shirt. Between the two dingy, perspiring windows there is a thin, creaking, rickety door, above it, green from the damp, a bell which trembles and gives a sickly ring of itself without provocation. Glance into the looking-glass which hangs on one of the walls, and it distorts your countenance in all directions in the most merciless way! The shaving and haircutting is done before this looking-glass. On the little table, as greasy and unwashed as Makar Kuzmitch himself, there is everything: combs, scissors, razors, a ha'porth of wax for the moustache, a ha'porth of powder, a ha'porth of much watered eau de Cologne, and indeed the whole barber's shop is not worth more than fifteen kopecks. There is a squeaking sound from the invalid bell and an elderly man in a tanned sheepskin and high felt over-boots walks into the shop. His head and neck are wrapped in a woman's shawl. This is Erast Ivanitch Yagodov, Makar Kuzmitch's godfather. At one time he served as a watchman in the Consistory, now he lives near the Red Pond and works as a locksmith. "Makarushka, good-day, dear boy!" he says to Makar Kuzmitch, who is absorbed in tidying up. They kiss each other. Yagodov drags his shawl off his head, crosses himself, and sits down. "What a long way it is!" he says, sighing and clearing his throat. "It's no joke! From the Red Pond to the Kaluga gate." "How are you?" "In a poor way, my boy. I've had a fever." "You don't say so! Fever!" "Yes, I have been in bed a month; I thought I should die. I had extreme unction. Now my hair's coming out. The doctor says I must be shaved. He says the hair will grow again strong. And so, I thought, I'll go to Makar. Better to a relation than to anyone else. He will do it better and he won't take anything for it. It's rather far, that's true, but what of it? It's a walk." "I'll do it with pleasure. Please sit down." With a scrape of his foot Makar Kuzmitch indicates a chair. Yagodov sits down and looks at himself in the glass and is apparently pleased with his reflection: the looking-glass displays a face awry, with Kalmuck lips, a broad, blunt nose, and eyes in the forehead. Makar Kuzmitch puts round his client's shoulders a white sheet with yellow spots on it, and begins snipping with the scissors. "I'll shave you clean to the skin!" he says. "To be sure. So that I may look like a Tartar, like a bomb. The hair will grow all the thicker." "How's auntie?" "Pretty middling. The other day she went as midwife to the major's lady. They gave her a rouble." "Oh, indeed, a rouble. Hold your ear." "I am holding it. . . . Mind you don't cut me. Oy, you hurt! You are pulling my hair." "That doesn't matter. We can't help that in our work. And how is Anna Erastovna?" "My daughter? She is all right, she's skipping about. Last week on the Wednesday we betrothed her to Sheikin. Why didn't you come?" The scissors cease snipping. Makar Kuzmitch drops his hands and asks in a fright: "Who is betrothed?" "Anna." "How's that? To whom?" "To Sheikin. Prokofy Petrovitch. His aunt's a housekeeper in Zlatoustensky Lane. She is a nice woman. Naturally we are all delighted, thank God. The wedding will be in a week. Mind you come; we will have a good time." "But how's this, Erast Ivanitch?" says Makar Kuzmitch, pale, astonished, and shrugging his shoulders. "It's . . . it's utterly impossible. Why, Anna Erastovna . . . why I . . . why, I cherished sentiments for her, I had intentions. How could it happen?" "Why, we just went and betrothed her. He's a good fellow." Cold drops of perspiration come on the face of Makar Kuzmitch. He puts the scissors down on the table and begins rubbing his nose with his fist. "I had intentions," he says. "It's impossible, Erast Ivanitch. I . . . I am in love with her and have made her the offer of my heart . . . . And auntie promised. I have always respected you as though you were my father. . . . I always cut your hair for nothing. . . . I have always obliged you, and when my papa died you took the sofa and ten roubles in cash and have never given them back. Do you remember?" "Remember! of course I do. Only, what sort of a match would you be, Makar? You are nothing of a match. You've neither money nor position, your trade's a paltry one." "And is Sheikin rich?" "Sheikin is a member of a union. He has a thousand and a half lent on mortgage. So my boy . . . . It's no good talking about it, the thing's done. There is no altering it, Makarushka. You must look out for another bride. . . . The world is not so small. Come, cut away. Why are you stopping?" Makar Kuzmitch is silent and remains motionless, then he takes a handkerchief out of his pocket and begins to cry. "Come, what is it?" Erast Ivanitch comforts him. "Give over. Fie, he is blubbering like a woman! You finish my head and then cry. Take up the scissors!" Makar Kuzmitch takes up the scissors, stares vacantly at them for a minute, then drops them again on the table. His hands are shaking. "I can't," he says. "I can't do it just now. I haven't the strength! I am a miserable man! And she is miserable! We loved each other, we had given each other our promise and we have been separated by unkind people without any pity. Go away, Erast Ivanitch! I can't bear the sight of you." "So I'll come to-morrow, Makarushka. You will finish me to-morrow." "Right." "You calm yourself and I will come to you early in the morning." Erast Ivanitch has half his head shaven to the skin and looks like a convict. It is awkward to be left with a head like that, but there is no help for it. He wraps his head in the shawl and walks out of the barber's shop. Left alone, Makar Kuzmitch sits down and goes on quietly weeping. Early next morning Erast Ivanitch comes again. "What do you want?" Makar Kuzmitch asks him coldly. "Finish cutting my hair, Makarushka. There is half the head left to do." "Kindly give me the money in advance. I won't cut it for nothing." Without saying a word Erast Ivanitch goes out, and to this day his hair is long on one side of the head and short on the other. He regards it as extravagance to pay for having his hair cut and is waiting for the hair to grow of itself on the shaven side. He danced at the wedding in that condition.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Check out the author's bookstore to browse and purchase both printed and e-book editions!